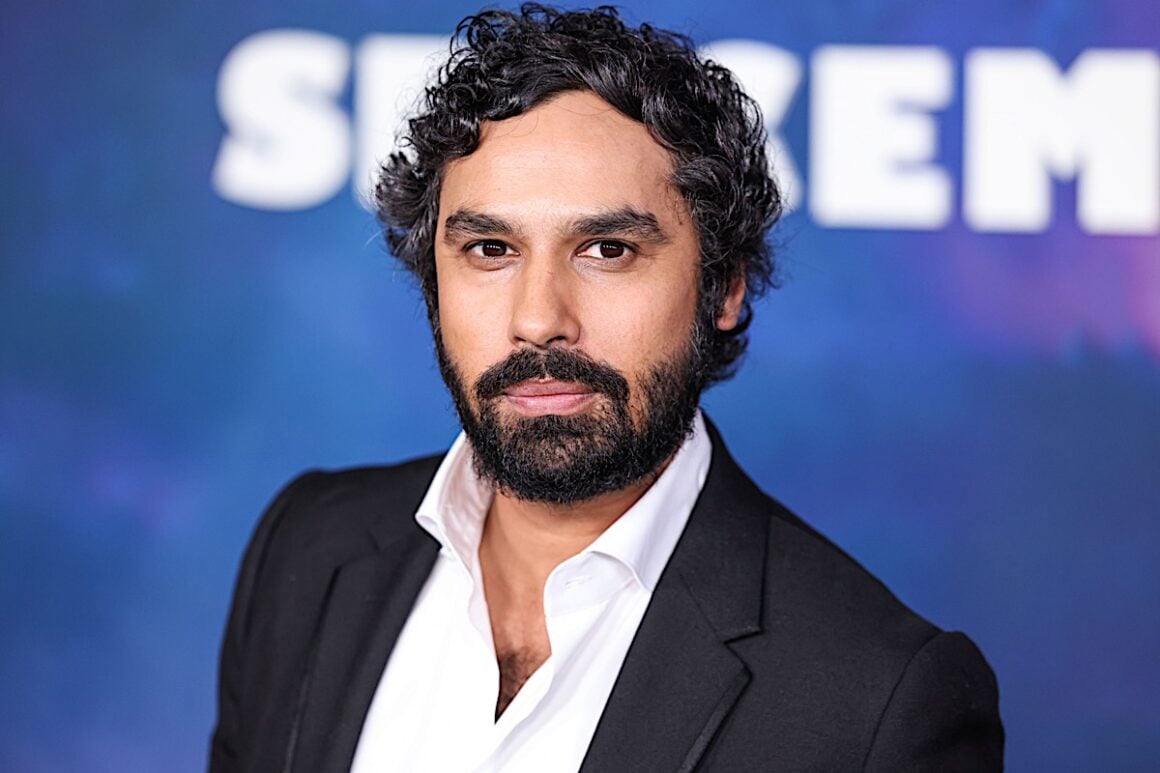

For filmmaker Jeffrey D. Simon, storytelling has always been a hands-on affair, whether he was composing original music for a school play or art directing blockbuster films like Venom and Spider-Man: Homecoming. But it was in a snowy upstate bookstore, with just eight crew members and two actor-musicians, that Jeffrey rediscovered the magic that first drew him to film: the power of singing truth, live and unfiltered, directly to the camera.

Now, with You Don’t Say, a genre-blending, bookstore-set short now streaming on Omeleto, Jeffrey and his production company The Barn are quietly revolutionizing the movie musical. Think fewer sequins, more storytelling. Goodbye lip-syncing, hello live vocals. These are musicals made on a human scale and are intimate, inventive, and buzzing with emotion.

In our exclusive interview, Jeffrey opens up about his journey from Chicago community theater to the heart of Hollywood, why all movies could be better as musicals, and how a “little E-MU synth box” started it all.

How did you develop your passion for storytelling and moviemaking?

We had this amazing community theater in my Chicago suburb called the Children’s Theater of Western Springs where they gave students free range to put on whatever shows we wanted and do all of the things. I basically lived there from seventh grade until I graduated high school. I learned all the ways that shows get put together, from set design to sound design to stage management. When they found out I played the piano, they asked me to accompany Merry Christmas Strega Nona.

The first time I ever heard somebody sing a song I wrote was for a theatrical adaptation of the Salman Rushdie novel called Haroun and The Sea of Stories. It wasn’t a musical, but the director wanted songs and asked me to write them. I had this little E-MU synth box that could approximate an orchestra. I’m sure by today’s standards it would sound crazy digital—or maybe be hip 90’s nostalgia, ha! But having somebody sing something that I’d written … that was the thing that inspired me most.

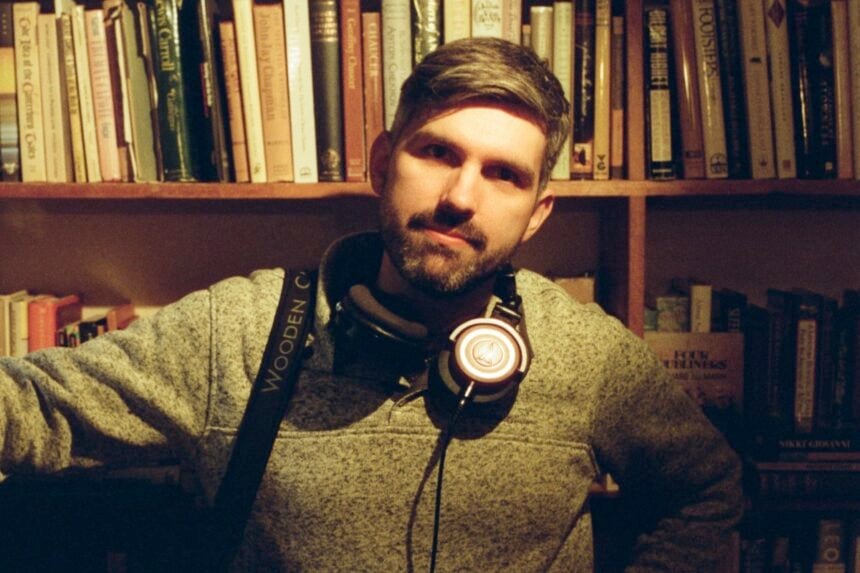

How did you get involved with The Barn?

For undergrad I went to SCAD, where I thought I’d keep doing both design and music together, but their main music composition professor (who had convinced me to go to the program) left right before I started. So, I kind of fell into the design world. It’s such a wonderful school for art and design and I was mesmerized by it all. I was pretty successful right away when I moved out to LA and worked my way up as an Art Director eventually having a pretty steady gig with the incredible designer Oliver Scholl. I did a bunch of huge projects with him including Spider-Man: Homecoming, Venom, and even spent a year in London working on Edge of Tomorrow. That experience was both wonderful and left me wanting further creative freedom. I had stories of my own to share, and I thought that going away from the industry for a while was the best way to come back reinvented. So, I stepped away from the Art Department and went back to grad school at USC for directing.

Going back to school made me dive deep into the stories that I wanted to tell that I thought weren’t being made. For one of the early class assignments, I made a five-minute musical short called Spark and it turned out GREAT. It showed me that this is the kind of movie that I should be making. It combined everything I love: music, storytelling, and visuals, into what I now consider to be the ultimate artform, the movie musical.

I spent the rest of my three years honing those skills. The one thing that I hated most was lip synching. I felt like this ruined the magic of watching somebody sing. It really took me out of it. And Les Mis had just done a huge spectacle with live singing, so I thought how hard can it be? I worked with the incredible sound design professor Steve Flick (Academy Award for Speed) to figure out how we could record vocals live on set on a student budget.

The end result was my thesis film, Steam!, which also served as the proof of concept for what became The Barn. I begged my co-founder Matthew Andrews, who was not at school with me, to come produce my thesis. We took a small crew of about 25 people to the mountains of New Mexico and filmed in and around a historic steam locomotive. That project solidified for us both that Movie Musicals were our calling, that this is what we wanted to do for the rest of our lives. As soon as I graduated we founded The Barn.

You Don’t Say blends seven different musical genres. What inspired that creative choice, and how did you make them all feel part of one story?

I’d love to say that I had the idea, but the truth is that Matt and I put out a call on Instagram for people with short musical ideas and A. J. Freeman and Sam Balzac replied with this adorable script. I could immediately picture how it would work as a short musical. It was originally written as a calling card for them to perform on stage, showcasing their songwriting talents. The magic was supposed to be implied. But when I read it I couldn’t help but picture a crooked dusty old bookstore with practical match cuts and costume changes and everything you see in the film.

I was never worried about the piece working as a whole, even though all of the songs are quite different. I knew A. J. and Sam’s performances would be the foundation. Their voices bridge the differences in each song. And our fabulous music director and orchestrator Kyle Acheson tied it all together sonically.

You recorded every vocal live on set, which is something rare even in major studio musicals. What drew you to that approach, and how did it change the performances?

I firmly believe that lip synching is the worst thing you can do in a musical, at least for the types of stories I want to tell. To me lip synching takes you out of the emotion of the scene. How can you as an actor know what you’re feeling a month before you shoot in a recording studio? You end up with wooden performances that indicate towards the truth, but never quite get there.

This was the fourth film we’d done with live singing so we’ve gotten it down to a science. Luckily A. J. and Sam come from theater so having to sing live and hit the notes while performing is something they were both used to. I’m not sure they were used to the 12+ hour days, but they honestly crushed it.

The film was shot in a bookstore with a team of eight people. How did that intimate setting shape the storytelling?

I personally love small crews. I’d spent years working on movies with hundreds of people where you hardly know everybody’s name even in your own department. We shot You Don’t Say in upstate New York during a January snowstorm, so nobody wanted to go outside which forced this immediate bonding. When you have this size crew everybody helps out in other departments, which always makes for exciting discoveries. The amount of people helping land that tumbleweed in exactly the right place was comical.

The film feels as much like a love letter to books as a romantic tale of two friends becoming more than that. How important was it to use books as a narrative device?

Bookstores are romantic to me. There’s something about being surrounded by the creativity and life work of so many hundreds of people that’s endlessly inspiring. I think we can all learn from reading/hearing/listening to other people’s stories. It helps us relate to people from different places/backgrounds/worlds we may not have had the chance to meet. Seeing other perspectives helps us contextualize what’s right in front of us.

You’ve described You Don’t Say as both escapist and deeply emotional. What do you hope audiences take away from it?

I hope that audiences have fun. We’re making entertainment and that’s the primary goal—to entertain. But the film also asks the universal question of why we make and enjoy art in the first place. The answer, I think, is built into its ending. We create stories to better understand our own feelings, to learn to communicate more honestly, and to feel more connected to the people around us.

The Barn’s motto seems to be “movie musicals, reimagined.” What does that mean to you, and how do you see your work pushing the genre forward?

I love that! I might steal it: Movie Musicals, Reimagined. I think Movie Musicals get mistaken for a genre, when they’re actually a form, sort of in the way that animations get mistaken for kids’ movies. You can have horror musicals, historical epic musicals, musical comedies, action-adventure musicals, the possibilities are endless. I’m personally interested in what small scale musicals look and feel like.

The feature I’m developing, West of Western, is a long-distance love story about two gay men who live on opposite sides of Los Angeles. It’s about the things that go through your head on the long drives in traffic. It’s about the magical nights spent climbing the stairs of Echo Park eating street tacos. The music is like what a singer songwriter might make about their own emotional rollercoaster of dating and falling in love. How can I harness the palette of artists like Bon Iver and Lorde into a musical movie?

You’ve said you believe “all movies would be better if they were musicals.” Can you unpack that idea a little?

There’s an old cliche from the golden age of Hollywood Musicals that says, “if you can’t say it, sing it; if you can’t sing it, dance it.” It basically describes the emotional escalation in a well-structured musical. Dialogue expresses ordinary emotion, song expresses heightened emotion, and dance expresses what words or even sometimes melodies can’t. Music and movement take over where speech fails.

So, if you’re making an ordinary movie or what I call a straight movie (which to the gays in the audience has a certain connotation of boringness) you’re not painting with all of the possible colors. Musicals are obviously not realism, but neither are movies. All that matters in the end is what a movie makes you feel, and songs take you beyond ordinary emotion.

Why do you think audiences are ready now for a new kind of musical—smaller, more personal, and emotionally raw?

I certainly can’t predict what audiences want, but I know what I want and what I’ve not seen done before. I love stories that take me deep inside the realities of interesting characters and let me stay there for a while feeling what they feel. Musicalizing the internal dialogue of those characters gives us this beautiful set of tools to add layers of meaning and feeling. And as a species we love to apply meaning to the things around us. So hopefully the movies that we make will achieve that aim.

How do you balance artistic risk-taking with the realities of indie filmmaking?

I went from making the biggest least risky movies possible (superheroes) to the most niche (indie movie musicals). So, I’d say my eyes are open to the brutal realities of what it takes to get any project off the ground, be it a short film or a feature. Matt and I founded our company right at the top of the pandemic, which of course derailed many of our plans, but it did teach us how to be scrappy and find ways to keep our musicals moving forward while also taking on commercial work. We have a sibling company The Silo to help us pay those pesky bills.

You Don’t Say is part of a larger slate of shorts, including Spit Me Out and the upcoming feature West of Western. How do these projects connect in tone or theme?

The direct tonal comparison is from Steam! to West of Western, because in both of those cases I’m the writer, director, composer, and lyricist. They’re both queer stories inspired by my own life and very personal projects to me.

As far as the rest of The Barn is concerned, we’re painting with a large palette and taking big risks to see what works and what doesn’t. If a project excites us, that’s all that matters. And of course, it has to hit all the points on our movie musical manifesto. Yes, we know it’s a little pretentious, but it has a nice ring to it, no? In short, there are four tenets: 1. Songs are in service to the story, 2. Characters don’t “perform” songs, they are the songs, 3. No Lip Syncing, 4. Stories are crafted for the screen, not the stage.

What advice would you give to filmmakers who love musicals but don’t have the budget or backing of a big studio?

Call us! We’re building a community of musical creators, lovers and fans.

What’s one moment during You Don’t Say’s shoot that reminded you why you fell in love with musicals in the first place?

My favorite genre is the Western. I love the shot that pushes in on Lilith as Herbert dies in her arms. Just beneath the hilarious absurdity there’s an ache that pulls at my heart, wanting this fantasy of love and heartbreak to be a reality, but knowing that it’s only a dream.

Keep up with upcoming projects from The Barn on their website (and check out The Silo Studio too.). Follow Jeffrey on Instagram.

MORE POP CULTURE HEADLINES